The foundations of lifelong health, both physical and mental, are built in early childhood.

Ross Thompson, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at University of California, Davis. Dr. Thompson’s expertise focuses on early personality and socio-emotional development in the context of close relationships. His current projects include the development of emotion regulation in preschoolers; depressive symptomatology in relation to infant-mother interaction; and toddlers’ social and emotional development.

What is the scientific basis for prenatal and early child development?

We have gained considerably greater understanding of the importance of early experiences (beginning prenatally), how they become incorporated into young children’s behavior and their biological functioning, and the longer-term consequences of these influences. We are beginning to understand how the flexibility of children’s development offers opportunities to intervene if early experiences are aversive.

With respect to early adversity, the important story is this: Infants and toddlers from difficult circumstances are already at a disadvantage. It’s not just about how much their parents are reading, singing and talking to them, but also because other factors—like chronic stress and poverty—are keeping children from thriving. For example, the research on early brain development and the impact of toxic stress give us new ways to understand kids in poverty. By paying attention early, we can prevent a multitude of adverse biological effects from early difficulty.

How are the early years important to health?

The early years are the foundations of physical and emotional health. Early experiences do a great deal to shape brain architecture. Research is showing increasingly that early experiences affect a wide variety of biological systems. These systems influence immunological functioning, strengthening or impairing the body’s capacity to cope effectively with infectious disease. These systems also influence learning, attention and self-regulation. Beyond physical health, the early years are when significant relationships develop with caregivers who provide a sense of security, protection and support to a young child. These relationships are the cornerstone for a young child’s emotional health, and the sense of safety or vulnerability created in the context of early relationships also shapes brain development.

Why must we also focus on prenatal care?

The research on what is called fetal programming shows that heightened maternal stress and its neuro-hormonal effects have an impact on the fetus. The quality of the mother’s nutrition, medical care, the stress that come from economic adversity—some research shows that these can have long-term effects on the child’s development after birth.

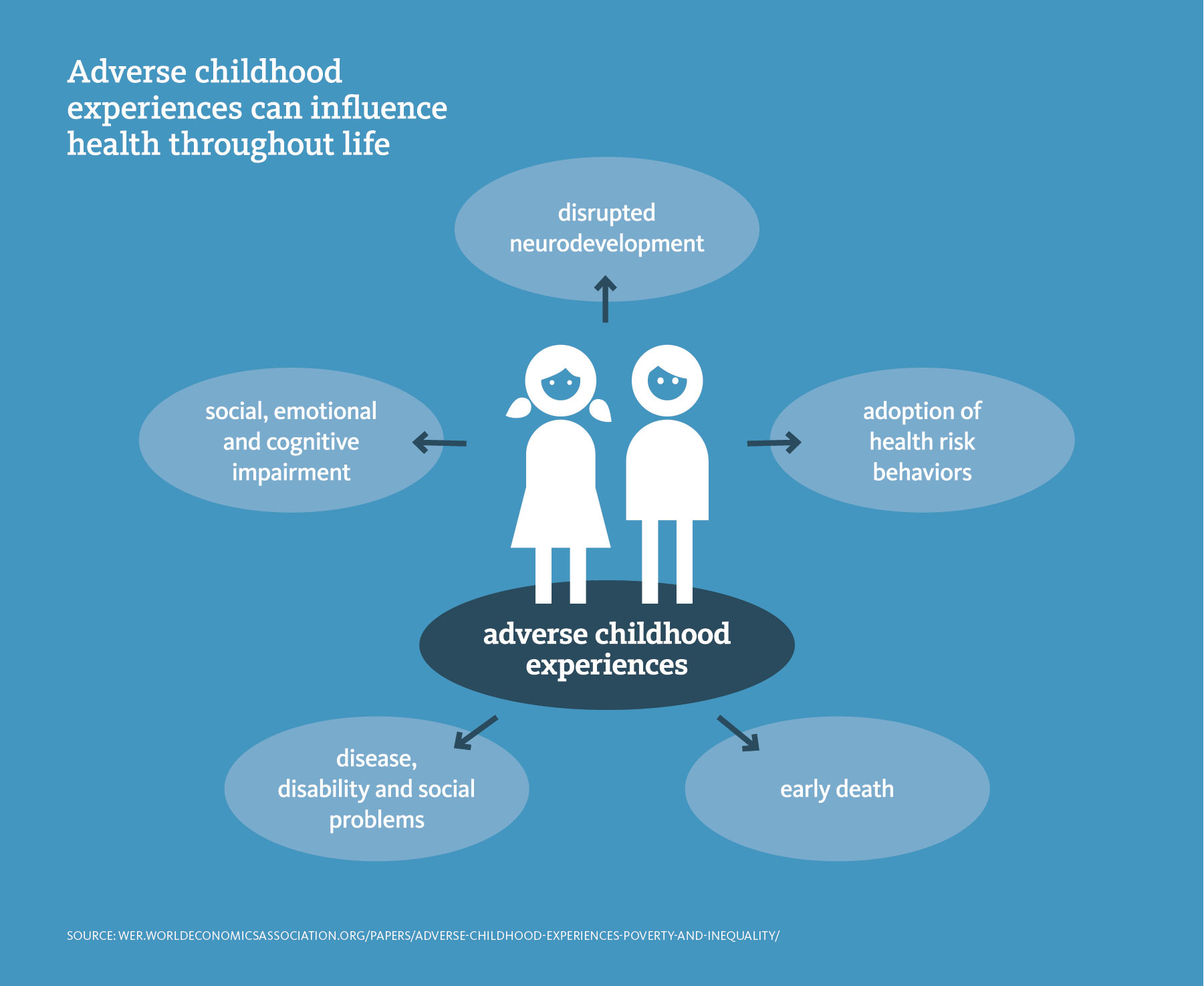

What are some of the health impacts of our earliest experiences?

In addition to the impacts I talked about earlier, there is considerable research on the effects of early stress on young children’s development. Early stressful experiences can have a profound impact on children. Stress affects kids’ ability to manage their emotions and impulses, and also their ability to focus their attention and thinking on new learning. Stress dictates the extent to which young children are vigilant for threats or danger, rather than being able to invest themselves comfortably in new learning opportunities. That’s a part of the early development story—the legacy of the first three years—that is important. It means that by age three, you can already observe the effects of chronic stress on young children who have grown up in families experiencing economic adversity, or neighborhood violence, or domestic upheaval. They are likely to be more reactive to perceived threat or danger, may have greater difficulty managing their feelings, and are less capable of self-regulation.

What about early cognitive stimulation?

Early cognitive stimulation—activities to stimulate language, thinking, memory, self-regulation, among others—is important. Vocabulary development, literacy development and language are impacted very early on. The ordinary daily experiences of young children with those who care for them provide stimulation for the growth of the mind. These relationships with the people who matter to a young child are important not only because of the cognitive inputs they offer—such as conversation, counting games, and answers to questions. They are important also because of the significance of these people to a young child, the confidence they inspire in the child to be curious, ask questions and be self-confident as a learner. It is, in other words, not just what a person does, but who that person is to a young child that stimulates the growth of young minds.

Why is it important that we protect newborns from stress?

It is important because a newborn’s brain is responding to signals about the world into which she has been born. Consider, for example, how early language learning develops. A newborn cannot know whether she’s been born in Los Angeles or Kiev or London or Tokyo. Therefore, the newborn’s brain is ready to learn any of the world’s languages—the child is figuratively a citizen of the world at six months. By 12 months, however, the child has had months of overhearing the language(s) in the home environment, so the brain becomes reorganized so that it can become an efficient learner of that particular language. And this helps to account for the vocabulary explosion that follows in the second year.

This story is not unique to language. The newborn also cannot know whether she has been born on the East Side or the West Bank. Just as the brain is sensitive to language input, it is also sensitive to the signals that indicate whether the world is dangerous or secure. These signals are conveyed by the stress the child experiences and the sensitivity of parental care. And just as with language, the brain organizes itself accordingly: to be attuned to threat or danger if these signals indicate that the world is dangerous, or to be attuned to learning and exploration if these signals indicate that the world is safe (and there are people who provide protection).

What kind of investments do we need for prenatal and early child development?

We must invest “patient capital.” I learned this concept when speaking with Alaskan oil executives, asking how they go about the process of exploration for new oil fields. They said that when they are investing, they don’t expect investments to pay off immediately. It takes a long time to develop oil fields. They are investing “patient capital” and know they will not see the payoff for maybe 5 to 10 years later. Investors and policymakers need to keep this in mind. The desire for an immediate return on investments in young children’s development is one of the reasons that it’s hard to get traction on early childhood issues. In contrast to oil company execs, most of us don’t appreciate that it will take time to develop learning skills, social skills and other competencies, and that there may be failures along the way. It takes a long time to develop a child. It’s the idea of being patient. It’s contrary to the policymaking nature of our country and yet it’s in line with everything that we know to be true with respect to development from prenatal to five years of age.

Any other thoughts on investing in the early years?

We have found that investing in healthy development can pay off. Earlier in the 20th century, many older adults were impoverished, in poor health, and with poor prospects for the future. Public investments in programs for seniors have changed that picture dramatically. As we turn our attention now to our youngest citizens, we are faced with the same compelling moral case for improving the circumstances of an important population who cannot do it for themselves. We invest in children because they are our future and we also invest in them because they are who they are, our own.

Jack P. Shonkoff, M.D., is a professor of pediatrics, and child health and development at Harvard. He is also the director of the university-wide Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University and chair of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. In 2011, Dr. Shonkoff launched Frontiers of Innovation, a collaboration among researchers, practitioners, policymakers, investors and others who are committed to developing more effective intervention strategies to catalyze breakthrough impacts on the development and health of young children and families experiencing significant adversity.

How did you begin focusing on early child development?

As a pediatrician, I began my career expecting to care for kids and families. Early on I saw pediatrics as a way to make the world a better place, to be involved in the care and protection of children. Over the years as I got more involved in the challenges facing young children, I realized that the answers to their health needs go beyond doctors’ visits and the hospital. And so I became more interested in broader social policy issues. I have come full circle, trying to marry neuroscience, politics and policy to see how we can better create a more supportive world and environment for young children.

Which is more important: nature or nurture?

Development is influenced by an interaction between nature and nurture. Everyone is born with a unique genetic predisposition, but development is dramatically influenced by personal experience and by the environment in which children live. There’s no such thing as nature without nurture or nurture without nature.

Which areas of development need the greatest attention in the early years?

We must pay greater attention to the social and emotional development of young children—not instead of the more traditional focus on intellectual and language development, but on par with it. A great deal of brain research tells us how emotions are embedded in brain architecture and function. Early literacy experiences are crucial for young children, but they’re no more important than paying attention to children’s social and emotional well-being.

How do we optimally prepare children to be ready to succeed in school?

Children are born ready to learn! We don’t need to make them ready to learn. We don’t need to teach them how to learn. They are wired to learn from the beginning. They’re wired to experience and master their world. Our focus was less on a scientific formula for igniting a passion for learning in young children, but drawing on science to show how children can’t help but want to learn about what’s going on around them. Our job is to provide the best environment in which each child can pursue his or her development as far as it will go.

What do you see as a challenge in prenatal and early child development right now?

Scientific knowledge is increasingly informing the way programs are set up, the way policies are established and how parents raise their children. But these best practices must be a starting point, not a destination. The most striking missing piece in the fields of early childhood intervention and poverty reduction is the absence of a dynamic research and development dimension to support the design and testing of new strategies to produce substantially larger impacts than anything we have ever achieved. We need to do more with the science that makes the case for investment in early years. We need to use that science to stimulate fresh thinking and to advance our progress toward breakthrough outcomes, particularly for children and families facing the greatest adversity.